To Refine Results, Raid the Classics (Issue #31)

An interview with artist Adrian Pocobelli

“10 Symptoms of Liver Damage” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

1/1: Please introduce yourself.

Adrian Pocobelli: My name is Adrian Pocobelli. I grew up in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, which is in Canada’s Midwest. I later moved to Montreal, Toronto, and now Berlin. I studied art and English literature as an undergrad and did a Masters in English. I’ve worked as a graphic designer, editor, and now, podcast host and artist.

1/1: What art have you been working on lately?

Adrian Pocobelli: I like to work on two to three projects at once. I’m working on an update to the “Secret History of World War 3” series, where I use screenshots of the news as subject matter for artworks. I’ve recently been working on the “Promoted Stories” series, where I sample from trashy corners of the internet with different kinds of screen outputs, and the “Pixel Art Sketchbook,” where I draw various objects and scenes using dithering and a square brush.

1/1: Can you describe your workspace and how it influences your art?

Adrian Pocobelli: Mobile. I do the great majority of my artwork on an iPhone or an iPad. Later, I “master” the work in Photoshop on my laptop, but I almost always start from my phone or tablet.

Working mobile is integral to my entire workflow as an artist. I feel that the small surface areas of a phone or tablet, relative to your typical canvas, creates a fresh compositional style. I also feel that it fits the zeitgeist in that these objects—phones especially—are ubiquitous, everyday objects, which I think makes the works a bit more relatable and relevant.

“Celebrities Raised in Cults” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

1/1: What tools do you use? Do you work with any special devices or tools unique to your creative process?

Adrian Pocobelli: As far as hardware is concerned, I primarily use my iPhone and iPad, but the laptop is always the finalizer. I use several different kinds of software, where I use a lot of layers and masking to take advantage of processes that are uniquely available to a digital environment.

I also use the magic wand and the pencil tool, as I feel they both create inherently digital marks. The magic wand also adds a touch of randomness, as you don’t know exactly what will be selected before clicking the mouse.

I find it very powerful to work across different hardwares and softwares—exporting in a very general sense—to give an image a feeling of being unique and organic—what you might generally call its style or personality. I like my work to be recognizably mine, in the case that you haven’t seen the work before but are familiar with my work.

“Meghan & Harry” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

1/1: You created a book-length illustrated series of artworks about Thucydides' “History of the Peloponnesian War,” which includes some gorgeous digital art. What led you to pick that topic?

Adrian Pocobelli: Thanks. I’d been watching a series of lectures from The Teaching Company (later the Great Courses and now Wondrium) on Thucydides’ “History of the Peloponnesian War.” It’s considered the first “scientific” history book in the Western tradition, where the historian is largely atheist in outlook; in other words, he was looking for real-world causes of events rather than attributing events to the gods or supernatural forces.

Without the lectures, it’s a fairly impenetrable book, which is why it’s been a specialty only of classics scholars and military historians and almost nobody else until the nineteenth century. Since then, there’s been a large amount of scholarship on it, but what’s interesting is how little attention it’s gotten in the history of painting, which I suspect is because of the impenetrable nature of the book.

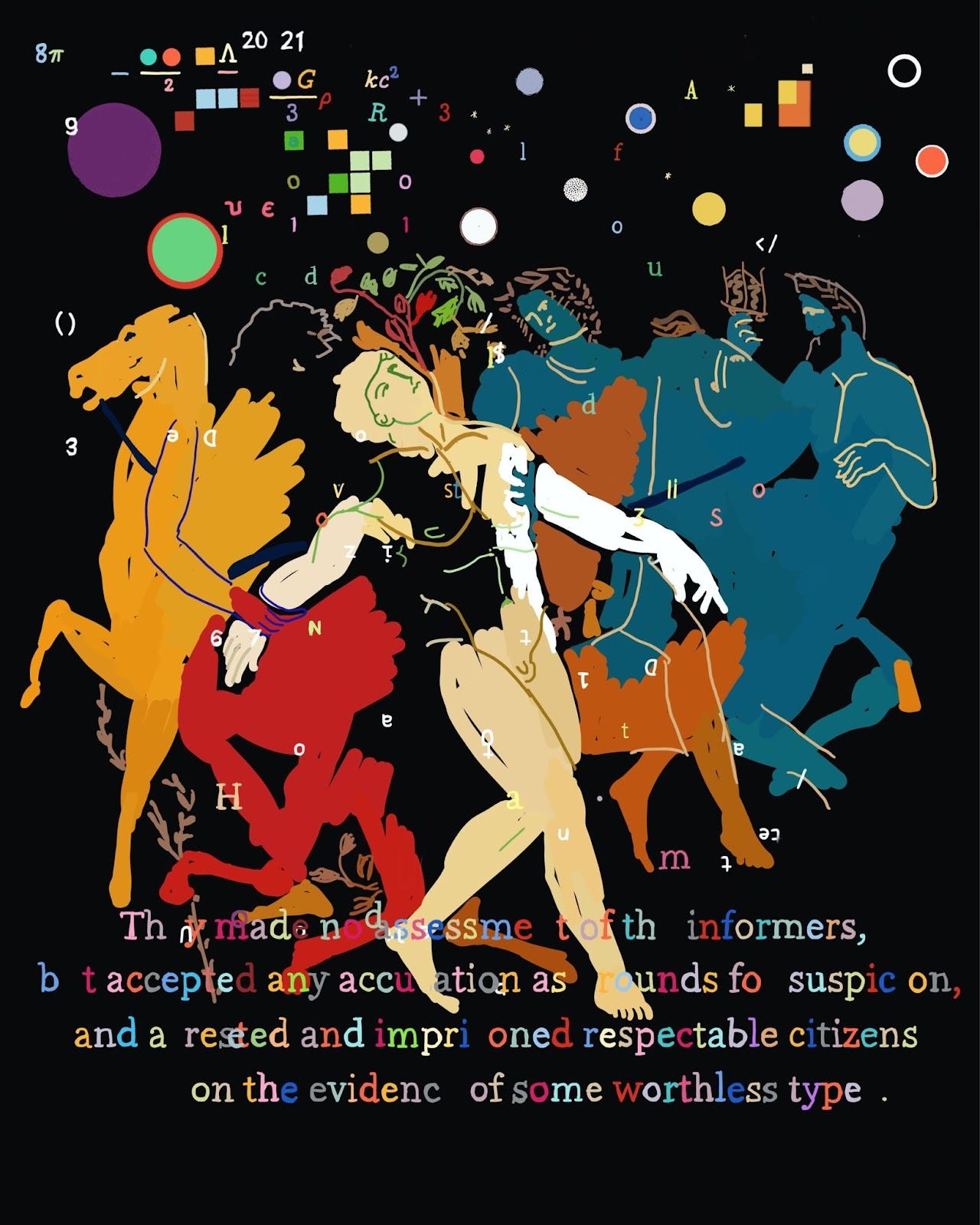

“The Peloponnesian War, Book 6.53-6.58 (The Story of Harmodius and Aristogiton)” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

Today it’s considered essential reading in terms of helping understand military strategy (both on land and on sea) and, probably most importantly, why people go to war. Great books are one of the big subjects in the history of art, as we see from depictions of the Bible or major events from Ancient Rome—for example, as found in the much more readable Livy and Plutarch. Greek myths are also a major subject in narrative painting over the centuries, which of course come down to us from several poets including Homer and Ovid.

All to say, Thucydides’ “History of the Peloponnesian War” felt like surprisingly virgin territory, considering its historiographical importance being the first “real” history book as well as its timeless assessment of one of the most important of all subject matters—war.

I began the series pretty randomly, one day trying things out using Greek vase imagery as a source, and before long I began making the series on my iPhone 6S. As I developed the concept, I began to add quotes from the book in the image, and then a third source of content from pop culture, the history of ideas, mathematics, or just about anything.

As a result, the retelling of the history, which I did largely chronologically, became a kind of alchemical magic act in my head, where I would juxtapose, or “mingle,” images and visual ideas that had likely never been mixed together before in a digital medium to create what Max Ernst would call flashes of inspiration. In this respect, it’s somewhat of a Surrealist project in that it uses heavy juxtaposition of disparate elements in new contexts, which of course is the main tenet of Surrealism.

1/1: How do you approach developing an idea into a finished piece? Can you walk us through your workflow?

“Intermittent Fasting” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

Adrian Pocobelli: This changed almost completely for me a little over ten years ago. I used to be almost religious about coming up with a concept and title before beginning a piece, and then I would try and make an artwork that would do justice to whatever grand idea I might have thought I had. Of course, this is an incredibly tedious way to work; at least it was for me, as it severely limits spontaneity and becomes 100% about execution of a particular idea.

After a few years of this, I was generally very unhappy with my progress. And so one day, likely out of sheer frustration, I had what I often call a Copernican revolution, where I would instead start a painting and give myself a deadline of, say, 24 hours to see what I could come up with. Needless to say, it was far more enjoyable to work that way and it allowed me to surprise myself along the route and do things I never would have imagined ahead of time. I’ve never looked back.

1/1: Can you describe a typical day in your artistic practice, including any rituals or habits?

Adrian Pocobelli: Usually it starts with a screenshot or some kind of imagery I’ve found on the internet and a coffee at a cafe. I’ll start laying things out and try out different experiments in the hope that I’ll come across something magical.

Once something starts to have poetic coherence, I’ll take a break and come back to it in a later session. Then I might go home and work on a different project that’s at a different stage on my laptop. Perhaps later I’ll then use my iPad to do some drawing in my “Pixel Art Sketchbook.” The next day, time permitting, I’ll pick up where I left off and do a similar routine.

“Jail cell” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

1/1: How do you feel about the impact of generative AI on the creative process? Do you have a favorite AI tool?

Adrian Pocobelli: Used in an open-minded way, I think AI tools are quite exciting and can help stimulate ideas and creativity. It took a few months for me to appreciate AI, but the key, as usual, is actually trying out the tools. Once you do this, you begin to realize how challenging it is to actually make a great artwork with it. So overall, I’m pretty excited about it; basically, it seems like a super sophisticated sampler-synth.

As far as tools, I keep things pretty simple and use Midjourney when I’m working with AI, although I’ve tried Stable Diffusion and Dall-E. I find the Blend prompt, which combines different images you upload, particularly powerful. My favorite thing to do is take previous artworks of mine and blend them together using AI. In a way, I think it helps me retain a heightened sense of authorship over the work.

“Kissinger” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

1/1: You wrote a dissertation on J.G. Ballard’s “Atrocity Exhibition.” What drew you to Ballard? I used to live in Shanghai, and I’ve always been fascinated by “Empire of the Sun” and how his childhood there during the Japanese occupation fucked him up but maybe to the benefit of his writing.

Adrian Pocobelli: Indeed, an awareness of Ballard’s upbringing is crucial to unlocking his unique perspective. As he said, to paraphrase, in the Lunghua prison camp, you saw human nature for what it was when the stage set of reality had been taken away.

At the core, I was always drawn to Ballard’s clarity and genuine insight. His descriptions and understanding of the world were relatable and seemed quite accurate yet simultaneously unfamiliar as I had never heard thoughts like that before. I think this is at the heart of his appeal.

There’s almost something self-evident about his insights once he states them, and they are very accessible, which makes them all the more persuasive. He also had a great interpretation of aesthetics and what made art important as well as its function, particularly with his emphasis on the importance of the Surrealists.

Ballard is in the tradition of artists who focus on the exploration and understanding of human nature; in that respect, he acts as a kind of doctor of the soul. As Burroughs put it in the preface to “The Atrocity Exhibition,” his analysis has the “accuracy of a surgeon.”

I see Ballard’s novel “The Atrocity Exhibition” as largely a response to Burroughs’ “Naked Lunch” and Ballard at his most distilled, boldest, and experimental. It’s an unapologetic work from a very deep thinker. And as much recognition as he’s gotten in the last 15-20 years, I still consider him very much under-appreciated—I can’t think of a thinker that understood the twentieth century as deeply or as accurately as he did while maintaining complete originality.

“Radar Truck” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

1/1: Are there any specific works of art (music, literature, film, etc.) that inspire or have significant meaning to you in your artistic practice?

Adrian Pocobelli: Music used to be of central importance to my overall aesthetics, but in recent years, my interest has tapered off significantly, although it’s starting to return very recently, like in the last few weeks. I’m finding a renewed sense of inspiration after not listening for several years—I’m finding it remarkably helpful to my creativity in ways I had simply forgotten. A good set of headphones is surprisingly important.

Other than that, I tend to read classic works that you’ll find in your Penguin English Library or Modern Library editions from way back and a lot of podcasts on finance and geopolitics. I’m a bit of a hard news guy—I like to know what the global conversation is about.

As well, I’ll always owe a debt to V. Vale, the publisher of RE/Search Publications whose works helped fuse JG Ballard and William Burroughs to punk and new wave (e.g. Devo). He did a brilliant synthesis connecting different facets of the counterculture as part of a larger social movement, and he anticipated many cultural trends such as tattoos and piercings way before they became mainstream. I’ve met him a few times and consider him a friend, and he’s as open and friendly as you would hope.

I also owe a large debt to my friend Brian Cotts in Saskatoon, Canada, who introduced me to RE/Search’s books and JG Ballard’s works, Devo and Philip Glass, etc., at a pretty young age, setting me on what feels like a pretty unusual path.

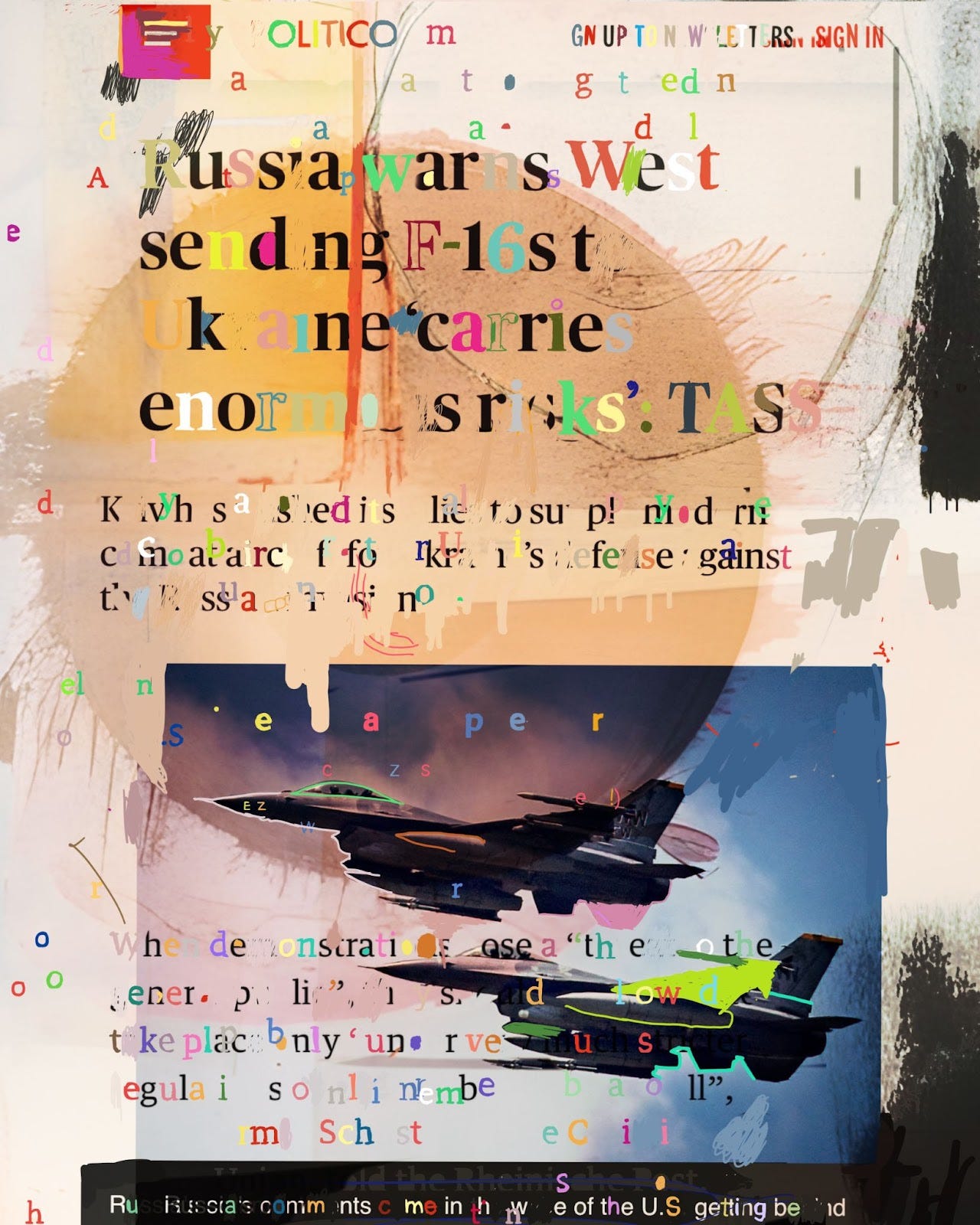

“F-16s” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

1/1: How do you come up with titles for your work?

Adrian Pocobelli: They tend to come up naturally as I’m working on the piece. Oftentimes, there is text within my work, so that can be a source for the title; otherwise, I just look at it and decide what feels right.

I’m a big fan of a stylish title. I’ve never bought into this trend by curators to remove title cards from exhibitions—it always seemed heavy handed to me, especially for twentieth-century paintings, which are often consciously titled by the artist just as a writer might title a poem or novel.

To find a Magritte without a title card, which I’ve seen repeatedly, is a small art crime in my world. It shows the curators involved don’t actually know what they’re showing, but just an opinion.

1/1: In an artist statement from 2020, you wrote:

“In a world drowning in images, the role of the artist is increasingly to provide commentary and analysis. The world doesn’t need another Picasso. It needs poetic clarity and synthesis from the thousands of images that pass across our visual field on a daily basis.”

Now, in this passage, it seems you were outlining an approach to your own artwork, but does this also hold for curation? Do you see curation as not just an analytical exercise but also as a kind of collaboration?

“Departure 3” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

Adrian Pocobelli: I’m very influenced by Ballard’s notion of the writer in the introduction to “Crash,” where in a world of “fictions of every kind,” the role of the writer (or artist) is to “invent the reality.” I see it as showing that art is quasi-scientific and can help us come to a deeper understanding of reality, the world, and ourselves.

The whole idea of being an artist to develop a specific style and milking that to your dying day seems a little empty to me. What can art bring to the conversation of serious people, like neuroscientists and physicists? What can it highlight about our world that only it can do and which gives us a clue into what is actually happening?

As far as curation is concerned, I see it largely as a creative endeavor similar to DJ mixing. It’s telling a larger story through the juxtaposition of artworks in a specific chronology—a story that has a kind of thesis of sorts. If artists are influenced by curations, then I suppose it can be collaborative, but in a very loose, informal way.

1/1: What draws you to NFTs and how do you see them as different from traditional art markets?

“Liftoff” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

Adrian Pocobelli: As an artist that often works digitally, NFTs enable me to sell digital art in a credible way. Before NFTs, the idea of putting a JPEG on a USB and giving it to someone always felt a little dubious and lacking in credibility.

As a digital artist before NFTs existed, the challenge was always how to make your work physical so that you could actually sell it. This was actually quite a useful challenge, as attempts to make physical renditions of my work ended up influencing my digital work, so I’m glad I had to try and figure it out. In many respects, I think the main conversation in contemporary art for the last 35 years has been how mediums translate and are modified by other mediums. This is what you find in the late Warhol and current work by Richard Prince.

I think digital art sales are turbocharged by social media as well. Platforms like Objkt, Zora, SuperRare and Foundation offer the same basic functionality as classic social media websites—follow, comments, notifications. So, weirdly, they become these futuristic social media sites of sorts, where instead of sharing your lunch, people share their art and the contents of their imaginations, and they often sell it too.

As far as the traditional art world is concerned, I see it as swimming upstream on several fronts. There are so many artists out there these days that it really does feel like the medium of painting is running out of ideas, which is partly why I think we see so many artists using airbrush and spray paint tools. But again, with digital, once you buy a tablet, phone, and laptop, and maybe a few apps, you’re good to go. Most people already have a phone and they can buy a couple of apps for $10-20—a pretty low cost to entry relative to traditional oil or acrylic on canvas, screenprinting, etc.

It seems like the role of the curator and the gallery are being conflated in the digital space, as there’s no need to have an actual space and employees managing the front desk. It’ll be interesting to see how it all plays out. The jury is still out.

1/1: Do you see yourself as a curator or critic or both? Is there a difference in the NFT space at the moment?

“Ascent 2” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

Adrian Pocobelli: Neither, actually. I consider myself an artist who talks about art. I think that’s why people, especially artists, find the videos interesting—because it’s coming from someone who’s actually been down similar roads and faced similar challenges as they have. Critics and historians almost never have that experience.

I often hear from artists, like just the other day at an art opening, “You’re the only person tonight who understands how difficult this is”—in that case it was image transfer with acrylic medium. Been there, done that, and it’s not as easy as it sounds. He really appreciated that someone understood the difficulties involved, which was somewhat core to appreciating the work.

I like the NFT scene because it’s new—it’s fresh, it’s young, and crypto seems to want to pave its own path, which I think is what the art world needs. Sometimes, it can take what seems to be a wrong turn aesthetically, but I much prefer a kind of innocent naïveté to the over-sophistication and ego of the traditional art world. There are going to be some stumbling blocks along the way, but as Devo says on “New Traditionalists,” we’re building new traditions…

1/1: For someone just getting into NFTs, what advice would you offer?

Adrian Pocobelli: It takes two days to two weeks to wrap your head around how digital wallets work, but once you do, you have everything you need to start selling digital art to a global audience, so it’s well worth it. Also, you should probably sign up for Twitter/X, as that’s where the crypto-digital art conversation is taking place and also where most NFT collectors hang out.

“pocobelli” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

1/1: What are you working on next?

Adrian Pocobelli: The next project I’m working on is a super low file-size pixel art version of Dante’s “Inferno,” probably for Bitcoin Ordinals. Other than that, I’m continuing to work on “Promoted Stories,” the “Pixel Art Sketchbook,” and the Screen Memories/Related Images/Composites series.

1/1: Could you show us some of your favorites of your work and tell us what they mean to you?

Adrian Pocobelli:

1.) “Car Ad #2”

This was the first work that I was proud of which I made on a phone—the iPhone 6S, which I call the first art phone because you could export across different apps and the processor was pretty powerful. This work is a combination of sampled brushstrokes that have been manipulated digitally and an internet ad for a car. It was all done at a bar over a glass of wine, and I’m still happy with the results. I’d call it a breakthrough work because it made me realize that I could make what I considered to be “serious art” on my phone.

“Car Ad #2” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

2.) “Study for The Peloponnesian War”

This was also made on an iPhone after I moved to Berlin—it was an early work from “The Peloponnesian War,” where I once again used sampled brushstrokes. It was another lesson that reminded me the more things you try, the more works are going to hit. It’s still one of my favorite works from the series.

“Study for The Peloponnesian War” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

3.) “Athenian Defeat at Delium”

This one is also from “The Peloponnesian War,” and I always liked the simplicity of it and the effective mark making. It had a nice loose feel and displayed characteristics that I would argue only result from using a finger on a touchscreen.

“Athenian Defeat at Delium” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

4.) “Athenian Success at Pylos”

This one I like because of the looseness, as well as the extreme juxtaposition of imagery, while still retaining a sense of unity. It’s another work that showed up from sheer persistence and hard work.

“Athenian Success at Pylos” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

5.) “q=Bellini+Doge”

This was the breakthrough work that transformed the “Related Images'' and “Screen Memories” series from an interesting experiment to something quite a bit more resolved. “Related Images” juxtaposes different representations of the same art piece that result from a Google Images query. While I was working on this version, I took a break and came back and realized that the work looked much more interesting with half of the layers in Photoshop turned off—an interesting case of being open-minded to aesthetic results that you may not have planned.

“q=Bellini+Doge” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

6.) “Madonna of the Goldfinch”

This work applies the same technique that you find in the previous work but on a single image. I call this series “Screen Memories,” where I work with a larger and more detailed canvas.

“Madonna of the Goldfinch” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

7.) “Bacchanal”

This was another breakthrough work where I combined dithered pixelated gradient and solid drawing in the same piece, which produced a pretty cool result. I still regularly use this technique. The source image was created by AI, so that also adds an interesting component and could be an entire series.

“Bacchanal” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

8 & 9.) “Mobile Tracking Station” & “Super Mario 3”

Through a series of processes, and after years of experiments, I found I finally had resolved my “Nostalgia Studies” series in these two works using Procreate to create an interesting digital drawing.

“Mobile Tracking Station” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

“Super Mario 3” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

10.) “Nuclear and Destructive”

This was also an important work for me and a bit of a breakthrough for my “Stories” series, where I take screenshots of the news as my subject. Here I used photographs of real paint in combination with digital techniques and processes in an attempt to make the news into art.

“Nuclear and Destructive” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

11.) “SH-101 Sketch”

This work was made quite quickly as I was just sketching in the “Pixel Art Sketchbook” and experimenting with different kinds of dithering (pixelated brushes). There was something kind of magical and carefree in the looseness of this, which, again, never could have been planned and just came from time spent in the studio.

“SH-101 Sketch” (image credit: Adrian Pocobelli)

Well done. A nice in-depth interview with the great Pocobelli👏